The World Bank has warned that Pakistan is in its tipping point on poverty as 40% of its population, accounting for 95 million Pakistanis, lives below the poverty line. This warning comes ahead of the elections. The Bank’s policy note, recently released, is meant to act as a guide for the new government that will take office after the elections for policy reforms. Underlying the Bank’s suggestions for the future is the fact over 12.5 million Pakistanis have fallen below the poverty line last year and who are struggling to meet their daily needs. The latest statistics show that poverty rose from 34.2% to 39.4% with more people falling below the poverty line of US$3.65 per day income level. With Pakistan facing serious economic and human development crises it is abundantly clear that the country is today unable to reduce poverty and living standards have fallen behind peer countries. This is certainly going to be a challenge in the near future, but the real problem is the capacity of any government in Pakistan to make a substantial difference has always been in doubt!

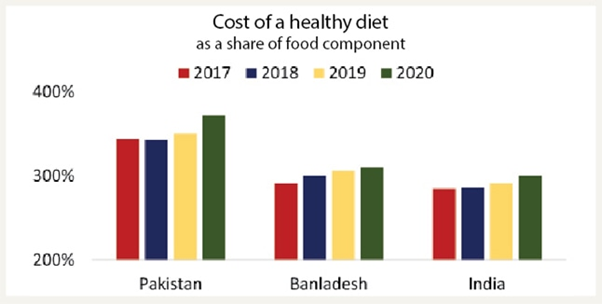

Najy Benhassine, Country Director for the World Bank in Pakistan, while releasing the policy notes on Pakistan, said this may be their moment to make policy shifts. Najy says Pakistan has been facing numerous economic hardships including inflation, rising electricity prices, severe climate shocks, and insufficient public resources to finance development and climate adaptation. The Bank’s policy note claims that the current model of development can’t reduce poverty in Pakistan, as the country has the lowest per capita income in South Asia and highest out-of-school kids in the world. Pakistan’s human development outcomes lag well behind the rest of South Asia and is roughly equivalent to those in many Sub-Saharan African countries with the costs disproportionately borne by girls and women. Statistics is this regard are telling as close to 40% of children under five years of age are stunted and Pakistan had the largest number (20.3 million) of out-of-school children in the world. According to the World Bank, Pakistan’s growth model has also resulted in periodic balance of payments crises driven by unsustainable fiscal and current account deficits that necessitated subsequent painful contractionary adjustments, slowing growth, reducing certainty and undermining investments.

Pakistan’s average real per capita growth rate was just 1.7% between 2000 and 2020, less than half the average for South Asian countries. Najy also observed that poverty reduction successes until 2018 in Pakistan had since been reversed. Pakistan’s poverty rate, according to the World Bank, for the middle-income line of US$ 3.20 per day had declined to 34.3% by 2018 from 73.5% two decades earlier, but had since increased to 39.4%. One of the proximate causes of the rise in the incidence of poverty in Pakistan was the 2022 monsoon floods which severely affected the lives and livelihoods of millions of people, especially in the Sindh and Balochistan provinces. The floods particularly impacted the poorest and most vulnerable, who are disproportionately more likely to live in flood-affected areas. Pakistan’s official estimates suggest that the floods led as many as 9.1 million people, into poverty.

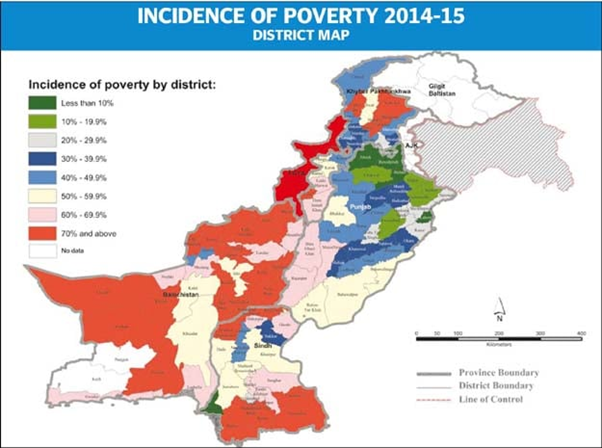

Poverty in Pakistan is also divided between the urban and rural areas. Between 2001 and 2015, poverty in urban areas declined at an annualized rate of 9%, compared with 6% in rural areas. In 2015, rural poverty was more than twice as high as poverty in urban areas and, despite a decline in the share of rural population, rural areas still account for four out of five poor individuals. Rural areas in Pakistan typically have higher poverty rates, while urban areas show higher inequality. Based on available estimates (2015), poverty is more than twice as high in rural areas (30.7%) than in urban areas (12.5%). Also, the incidence of poverty is spread unevenly across Pakistan’s provinces. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is the province with the lowest poverty headcount (18%) in 2015, while Balochistan accounts for the highest poverty rate (42.2%).

Pakistan, the seventh-poorest country in South Asia, has since 2001, moved approximately 32 million people out of monetary poverty, and poverty headcount rate (measured by consumption-based poverty estimates) dropped from 64.3% in 2001 to 24.3% in 2015. However, the poverty rate in Pakistan remains significantly high, and a large portion of the population is vulnerable, living at or close to the minimum poverty line. The World Bank has therefore, proposed that Pakistan’s government enhance revenue mobilisation potential at 22% of GDP against the existing rate of 9-10% and about 3% of GDP could be immediately recovered by properly taxing properties and agriculture which could contribute 2% and 1% of GDP respectively. Simultaneously, expenditures could be reduced through reforms by 1.3% immediately and about 2.1% over the medium term. Funds thus generated could be utilised in health, education and sanitisation sectors.

The World Bank has proposed shifting policies towards coordinated, efficient, and adequately financed service delivery, targeting the most vulnerable, in particular, to reduce abnormally high child stunting rates and to increase learning outcomes for all children, especially for girls. It also advises a shift from wasteful and rigid public expenditures benefiting a few, towards tightly prioritised spending on public services, infrastructure, and investments in climate adaptation, benefiting populations most in need. The World Bank has also asked Pakistan to tax its agriculture and real estate to achieve economic stability through steep fiscal adjustment of over seven per cent of the size of the economy. It is well known to international aid bodies that Pakistan’s heavy reliance on bank borrowing at high interest rates for deficit financing is one of the key factors behind high inflation. The World Bank has suggested that this could be arrested by reducing the government footprint in public sector entities that account for over 45% of GDP, most of them loss-making and needing public money to stay afloat.

The statistical picture painted above based on World Bank estimates and data clearly shows that Pakistan is in a dire situation and yet the caretaker government seems to be moving ahead as though nothing is going on. On its part the World Bank has done due diligence and warned of the consequences of neglecting the poor. Reforms have been suggested, but given Pakistan’s experience of such activity, this is likely to be a long-drawn process.