When it comes to China, the EU tried gently to ‘de-risk’ without ‘de-coupling’. Donald Trump put America first and launched a full-on trade war. Until last week, the UK took an approach that looked a lot like muddling through.

When it comes to China, the EU tried gently to ‘de-risk’ without ‘de-coupling’. Donald Trump put America first and launched a full-on trade war. Until last week, the UK took an approach that looked a lot like muddling through.

That luxury’s no longer available to it after the collapse of a high-profile espionage trial thrust relations with Beijing firmly into the spotlight. The UK’s public prosecutor last month dropped the case against two men accused of spying for the Chinese government, heaping pressure on Prime Minister Keir Starmer amid claims he should have done more to make sure it went ahead.

If a degree of obscurity was meant to help him quietly reset what King’s College London Professor of Chinese Studies Kerry Brown termed the “unwieldy mess” of Chinese-UK relations, the last few weeks have instead made them a political football.

Just this week, allegations of Chinese attempts to hack the British government and a warning by the head of MI5 about the “threat” posed by Beijing drew curt denials from China. Starmer had summarized his new approach as an imperative to “cooperate,” “compete,” and “challenge” — but now the Conservatives are leading opposition parties in demanding more emphasis on the last of the three.

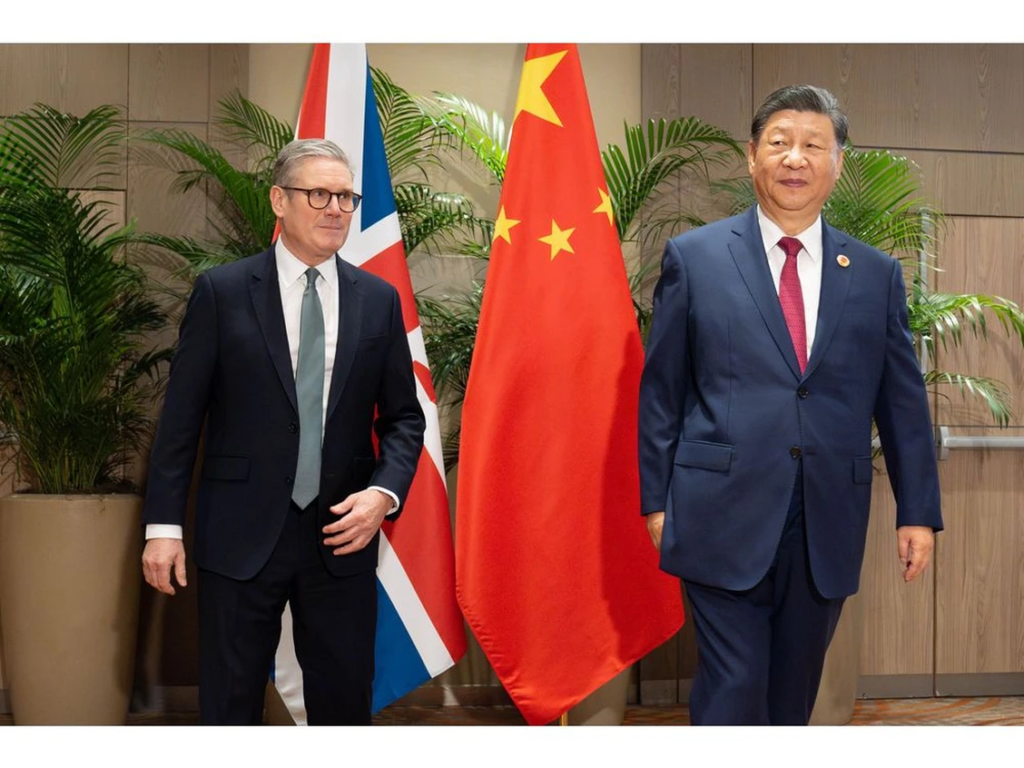

That is not where Starmer wanted to be when he set out to refresh Anglo-Chinese relations after winning power last year. Trips to the country by Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves and then-Foreign Secretary David Lammy had seemed to augur a new detente, even if a meeting with President Xi Jinping in Brazil did get awkward after Chinese officials removed journalists as soon as the UK leader brought up human rights.

Now, the souring of UK public opinion has helped the “impossible job” of balancing economic and security interests get harder because, as Brown told Bloomberg in an interview: “the relationship with China can go bad really quickly and is very hard to set right.”

The international precedents don’t inspire confidence. US President Donald Trump’s trade war has been characterized by an antagonism that the UK — and perhaps even the US — cannot afford. The European Union’s more cautious approach means its members now export less to China than to Poland, a nation with a gross domestic product that’s a 5% of the size.

And there are plenty of further flash-points for the UK ahead. On Thursday the government deferred to December a long-awaited decision about whether to approve a vast new Chinese embassy on the site of what was once the Royal Mint. That provoked an angry response as China’s foreign ministry warned yesterday that further delays would provoke “consequences.”

A person familiar with the prime minister’s thinking told Bloomberg he had wanted to see if a better relationship with China was possible after relations soured under the previous Conservative administration. A much-vaunted “golden era” pursued by former premier David Cameron gave way to suspicion following the Covid pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine.

After the Brexit shock to the economy and years of meager growth, Starmer’s team had sought to open up trade and increase cooperation in financial services, clean energy and artificial intelligence. The Treasury, Business Department and Foreign Office were on board with the thaw.

Other government departments, in particular the Home Office, Ministry of Defence and the intelligence community, take a more skeptical view. They are concerned at what they see as an increasingly hard edge of hostile Chinese activity in Britain and Europe, as well as its support for Russia’s military in Ukraine. They privately express alarm at the rapid pace of increase in Chinese military capabilities amid wider threats to Taiwan.

That internal divide has played out as the UK government mulls whether to approve the mega-embassy in the City of London, a key ask of Beijing, in the face of claims by opponents that it could be a spying hub and is positioned close to underground communications cables.

The UK’s high-level diplomatic visits have been less frequent since Trump re-entered the White House, with Starmer cautious not to provoke a more Sinoskeptic US. New Foreign Secretary Yvette Cooper had considered a China trip this year but now none is planned, according to people familiar with the matter. Recent events mean there are fresh doubts in Downing Street about whether Starmer’s own visit early next year will go ahead, they added.

The foreign office is concerned a tit-for-tat would impact UK hopes to refurbish its antiquated embassy in Beijing, albeit at a much smaller scale: the refurbishment in China has been tendered for £100 million ($134 million), while the Chinese embassy compound in London promises to be the largest diplomatic premises in Europe.

Starmer had been likely to approve to embassy, but that is now up in the air, government officials said. Several cabinet ministers have indicated they oppose the plans. But Beijing would view a rejection of the embassy application as a sign that relations had once again frozen over, another official said.

A path forward that now seems to the Brits so freighted with hazards may, ultimately be one over which they have little control. “China decides on its relations with the UK on the basis of whether the UK is useful to China, not because of changes in the UK’s China policy,” said Professor Steve Tsang, who runs the China Institute at SOAS in London.

“There is no reason to see them as zero-sum,” he said of the trade-off between economy and security. “The Chinese don’t.”